Preliminary note. This is an unusual text. Authors do not generally review their own works (although it is a practice not without its shady Victorian antecedents). And for the obvious reasons: assessments of significance and merit are best sought from expert third parties. And yet there are other things which readers of reviews seek, not least a summary of the book, its aims, methods, scope, and conclusions. And here the author’s voice seems as good as any other. Certainly, what an ‘autoreview’ lacks in objectivity it can make up for in intimate knowledge of the text. And authors are not without their own (sometimes very acute) sense of the strengths and weaknesses of their work. So what follows focuses on description, but does not shy away from anticipating criticisms (even if primarily to offer an authorial response to them). This is, after all, the way books are planned, written and revised in the first place.

Martin Hewitt, Darwinism’s Generations. The Reception of Darwinian Evolution in Britain, 1859-1909 (Oxford University Press, 2024), xv + 494 pages; £130. ISBN 9780192890993, DOI 10.1093/9780191982941.001.0001

In his Man and Superman (1903) George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) posed a question: ‘How old is Roebuck?’. ‘The question’, Shaw observed, ‘is important on the threshold of a drama of ideas; for under such circumstances everything depends on whether his adolescence belonged to the sixties or the eighties’. This passage heads the first chapter of Darwinism’s Generations and offers a motif for the whole work, which challenges scholars to put age back into the centre of understandings of the Victorian period. Not just age as in the experience of growing old, but age in the way Shaw was thinking of it, the way individuals are situated in the flow of historical time by their year of birth, and so age at any particular occasion, the distinctions of those who came to adulthood in the 1830s, or the 1850s or the 1870s.

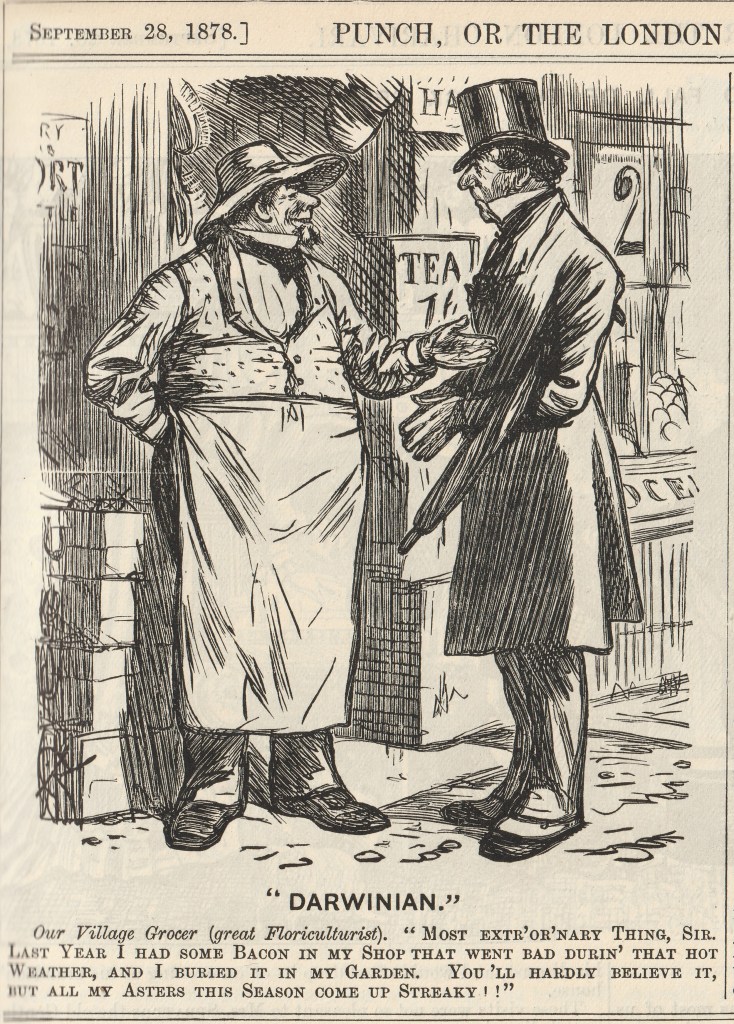

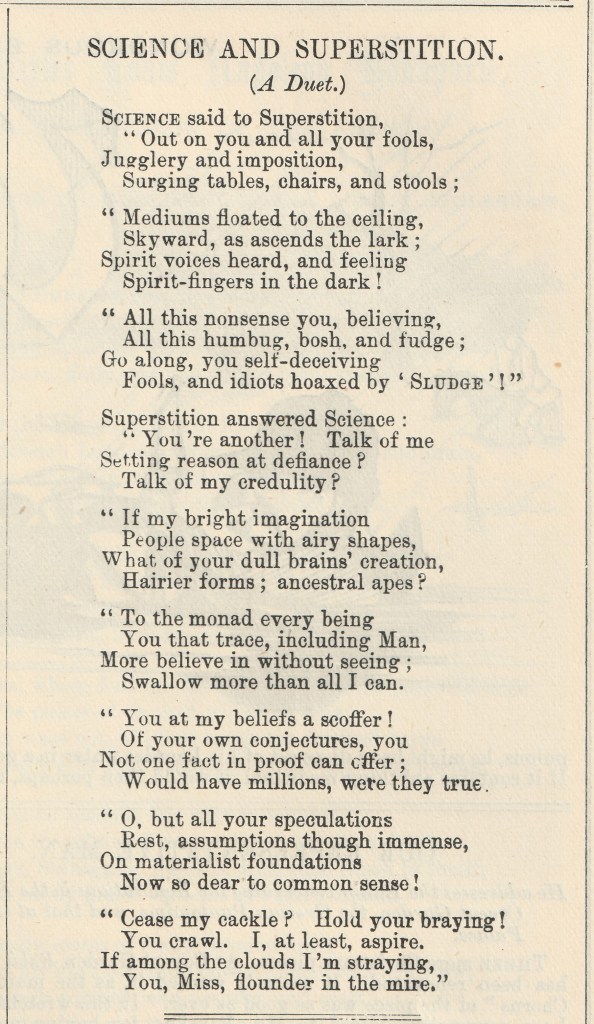

As the main title indicates, the subject matter of the book is attitudes towards evolution in Britain in the fifty years after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. This is already a crowded field. What is different here, though, beyond the sheer range of responses considered and the focus on the slightly unfashionable but still crucial question of belief, is that the reception study is not an end in itself, but a means to a much wider thesis. The publisher, conscious of the exigencies of online searching determined the foregrounding of evolution in the formal title of the book, but it is the intended title, emblazoned on the cover and used by the author throughout, Darwinism’s Generations, which more effectively communicates the book’s overarching intent: to explore the presence and importance of generational cohorts in Victorian Britain. The operating presumption is that if generational distinctions existed, they are most likely to be made visible in debates over the most charged and controversial topics, and nothing trumped Darwinism in this respect. Hence the Darwinism’s Generations seeks to explore the extent to which responses to Darwin and evolution were generationally modulated.

There is no shortage of intent here. This is a volume aimed at multiple readerships: historians, sociologists, literary scholars, those interested in the history of ideas, of reading and publishing, as well as science and culture. It is intended as a book which will not so much demand a reassessment of the nature of the ‘Darwinian revolution’, as seek to offer new ways of thinking about every aspect of Victorian culture and society, to challenge current understandings of the temporalities of historical change, and to shift the theoretical frames within which generational thinking operates across the social sciences.

Description

Perhaps as a result of all this ambition, this is not a volume for the faint-hearted or the hurried. Extending to nearly 500 pages, mobilising a cast of several hundred Victorians (and claiming an underlying prosopography of more than five times that figure), supported by almost 2000 footnotes, priced at an eye-watering £130, even in the current age of baggy scholarship, Darwinism’s Generations is a big beast. Even its individual components are heavyweights. An introductory chapter takes readers through the theoretical underpinnings and the later discussions, presents the generational schema being interrogated and outlines the configuration of ideas across which Darwinian debates raged, and a concluding chapter summarises the book’s findings and implications, and offers some important defences to some of the more obvious challenges the book is likely to face. In between, five core chapters, several of which weigh in like mini books in themselves, examine the phases of responses to evolutionary ideas in later Victorian Britain. Each chapter combines an exploration of the development of a new generational voice with a consideration of the continuities and shifts of existing generational dispositions and the contours of the inter-generational exchanges which resulted. The first two consider the reactions prompted by On the Origin of Species in the 12 years after its publication. The third and fourth look at the ways in which the publication of The Descent of Man in 1871, and then the death of Darwin in 1882, in combination with the emergence first of the High Victorian and then the late Victorians, added fresh layers to the debate. A fifth chapter considers the Edwardians and the way they contributed to what has frequently been described as the ‘eclipse’ of Darwinism in the years before and after 1900.

The weight of the underlying research cannot be questioned. The Bibliography indicates that substantial use has been made of over 30 archival repositories across Britian and Ireland, North America and Australia. Occasional references more than double this number. These are supported by extensive exploitation of the press and periodicals, national and local, and the transactions of metropolitan learned societies and provincial associations. And underneath these sits a very significant effort of prosopographical recuperation, because the focus of the argument requires that each interlocutor be situated generationally, that is, be placed via birthdate alongside their generational peers, something which itself has required assiduous detective work in press and periodical obituaries and the digital census records. It is true that the book’s 1500+ ‘respondents’ constitute a haphazard rather than random sample, mostly university educated males, most often scientists or clerics. But their accumulation has been guided by the needs of balance: social, gender and generational. There is a significant presence of women and of the lower middle and working classes. And there has been a deliberate attempt to move beyond the great and the good of the scientific establishment and the more overtly theological of Darwin’s opponents who have traditionally engrossed scholarly attention. Not all are directly referenced. But the responses of several hundred are explicitly cited, either in the main text or the extensive chapter endnotes. This method is described as one of ‘extensive reading’, something midway between the particularism of traditional close reading and the statistical abstractions of distant reading.

It is an approach not without its challenges. Some readers will baulk at the length which results. Although the book’s thesis is clear enough from the outset, and comprehensively summarised in the conclusion, there are no easy short-cuts for the impatient reader seeking to be convinced. The chapter structure is open to the objection that it replays a series of essentially similar generational emergences, and involves too much reiteration. But it does allow the reinforcement of the key message that the reception history of Darwinian ideas involved a set of multi-generational conversations in which modulation over time involved not just the equanimity brought by familiarity, or a persuasive act of conversion, but also a shift in generational composition and balance.

The decision to avoid any attempt at quantification is understandable, given that both the complexities and the fluidities of individual responses, and indeed the impossibility of fixing a single stable Darwinian doctrine, would make any quantifiable categorisations crude and dangerously atemporal. Even so, it leaves readers at the mercy of a potentially bewildering procession of voices: the Victorian great and good, not just scientists, but novelists, critics, religious leaders, politicians, dramatists, philosophers and poets, jostle with ordinary men and women, members of local literary or scientific societies, mutual improvement associations, newspaper letter writers, library borrowers, lecture attenders, who parade through the text as both illumination and evidence. A number of leading figures of Victorian intellectual culture, including A.R. Wallace (1823-1913),

T.H. Huxley (1825-95), the Duke of Argyll (1823-1900) and Leslie Stephen (1832-1904) provide a sort of narrative spine across the book. And some individuals enjoy a brief moment centre stage; figures like Charles Kingsley (1819-1875), Grant Allen (1848-99), M.E. Braddon (1835-1915), and G.B. Shaw himself. But most come into focus fleetingly, before the discussion moves on, and readers seeking a discussion of the responses of any specific individual may find this a rather breathless and at times superficial approach. Of course Darwinism’s Generations is interested in commonalities and shared characteristics, not difference, and it expects us to place individuals in the context of their generational position, to re-examine relationships with peers (and indeed mentors and disciples), to consider the collective dimension of individual actions and attitudes.

And there are advantages to the method. This is a reception study which takes readers deep into the nooks and crannies of the Victorian world, to the kitchen arguments in the terraced Oldham home of the suffragette Annie Kenney (1879-1953), the common rooms of Trinity College Dublin, the billiard room at Chatsworth House, even the Antarctic tents of Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912). And one with the broadest thematic range: the discussion addresses Victorian theology (of course), anthropology (inevitably), but also politics, economics, sociology, philosophy, theatre and literature. And it does produce an intensely personal book, full of flashes of the lived circulation of evolutionary ideas: including Henry Jeffs (1819–88), accountant and freemason of Gloucester, whose response to a lecture on evolution in December 1860 was to acquire two monkeys, dabble in comparative anatomy and almost lose himself in a maze of philosophy and metaphysics, the tramping stonemason, Lemuel Howard (1839/40-71), who threw himself to his death off a Carlisle bridge, leaving a journal ruminating on the horror of a Darwinian universe, or the barber of Arthur Balfour (1848-1930), who at one point was reported to have given him Darwinian diatribe, ‘the doctrine of evolution, Darwin and Huxley and the lot of them—hashed up somehow with the good time coming and the universal brotherhood, and I don’t know what else’ (quoted, 15). And if the analytic intent lends itself to slightly bloodless abstractions, there are at least vivid reminders of just quite how caustic the Victorians could be, sustaining a veneer of politeness to correspondents who were simultaneously crudely attacked to others, a register for which the late Victorian Darwinists seem to have had a particular penchant.

Arguments

The empirical ground covered may be well tilled, but this is not a book which can be dismissed as lacking originality or argumentative scale. Theoretically, it takes aim at the Mannheim-heavy model of generations which continues to hold sway nearly 100 years after it was first articulated. Various shortcomings of this framework are identified. Mannheim is implicated in in falling too readily into the trap of aligning with familial/genealogical generations of parents and children; in being overly pre-occupied with generational transmission and succession; in defaulting to a bilateral and conflictual mode. Darwinism’s Generations advances an alternative model in which sociological generations (and especially their periodicities) are uncoupled from genealogy, where generational cohorts are likely to comprise a birthdate range around 12-15 years, and which in consequence emphasises the importance of multi-generational interactions. Above all the new model rejects the tendency towards a subjectivist fallacy in contemporary generational discourses: the idea that a generation exists when (and only when) it thinks of itself as a generation. Conversely, here the central proposition is that it is generational location – generation ‘in itself’ – rather than generational identity – generation ‘for itself’ – which is the critical factor.

With these conceptual adjustments in mind, Darwinism’s Generations argues that when interrogated with age in mind, responses to Darwinism resolve themselves – at times loosely, sometimes over extended periods of time, always with exceptions where influences of religious belief, professional affiliation, gendered experience, or position on the cohort margins override generational drivers, but nevertheless in the majority of cases – in generationally distinct ways. The early Victorians, born roughly between the later 1790s and 1813, ranged themselves viscerally against the Origin and largely continued to deny the fact of evolution. The early Victorians could not reconcile evolution with their religious beliefs or escape the shock and anger which its challenge to their religious ideas had brought. In contrast, the mid Victorians (birthdates c.1814-1829) achieved an uneasy sense that compromise was possible, coming slowly to accept the fact of evolution, but generally remaining suspicious of natural selection, and committed to breaks in the evolutionary chain at the creation of the universe, the origins of life and separation of humanity from the rest of Nature in respect of morality and intellect. The mid Victorians were increasingly anxious to distance themselves from what they saw as the unreasoning hostility of the early Victorians, but were still inclined to perform differences over Darwin as fundamental conflicts. Meanwhile, the high Victorians (1830-45) were uninterested in these sorts of intellectual gymnastics. Identifying as Darwinists with the zeal of converts, they tended to make allegiance to Darwinism a fundamental test. Their underlying presumption was of a single unitary evolutionary process in which divine action, if necessary at all, was confined to first cause. They embraced Darwinian dynamics as unlocking the mysteries of the natural world, and as fundamentally altering the metaphysical context of all serious thought.

The shift to the late Victorians (1846-1859) was a shift from acceptance to appropriation: they shared the high Victorians’ belief in the unitary evolution of human and animal, but as a given, in fact as a matter of commonsense, rather than as a point of contention. The evolutionary commitments of the late Victorians were less emotionally charged, their beliefs a matter of discipleship and not mission. For them, the critical question had ceased to ‘whether’ and had become ‘how’, and their priority not controversion or conversion, but codification. They squabbled between themselves and with the high Victorians over who could claim Darwin’s imprimatur. While the mid and high Victorians had continued to be concerned primarily with the theological implications of evolutionary thought, for the late Victorians the vital implications of Darwinian thought were social and political. Finally, the move to the Edwardians (1860-75) is to move into a post-Darwinian phase: not that Darwin was generally thought wrong, just that he was insufficient and increasingly unimportant, no longer a vital guide to the really important questions of evolutionary biology. Abandoning the sectarianism of the late Victorians, the Edwardians often slid into indifference, and at times into scepticism.

Critical here is recognition that these patterns did not extend to stable or self-conscious generational identities of the sort visible by the time of the first world war. Victorian culture was saturated with generational languages, and it as has long been recognised that genealogical tensions between parents and children and the sense of generational division that resulted repeatedly played a significant role both in individual identities and in cultural change. Each of the chapters reinforces the ways in which differences of memory and observation, of educational experience and intellectual influence, and of career opportunities, all created specific generational locations that could have structural effects even without generational consciousness. In support of this Darwinism’s Generations draws on not merely attitudes and beliefs, but also multiple instances of generational behaviours, not least in brief vignettes of generational cohesion and conflict, the coterie which formed the nucleus of the Halifax Scientific Society, the Lux Mundi group, the museum reformers of the 1880s, or the evolutionary committee of the Royal Society in the 1890s and 1900s.

All this means that there was no ‘Darwinian revolution’ if by this we mean the rapid spread of an essentially Darwinian understanding of evolutionary history. The apparent judgement of much recent cultural history that within a few years after the appearance of the Origin contemporaries were convinced of the world’s evolutionary history and by Darwin’s explanation that this evolution was driven by the process of ‘natural selection’, cannot be sustained, not even within the narrow bounds of academic science. On the contrary, resistance to Darwin’s ideas was not just vociferous in the short-term, it was stubbornly durable. The evidence is that before 1871 the spread of Darwinian conviction was extremely limited, especially for those born before 1830. Even those within the Darwinian inner circle – Charles Lyell (1797-1875) for example – found acceptance hard. Thereafter more and more came reluctantly to some accommodation with evolution, but generally, at least amongst the older generations, without accepting natural selection as a sufficient explanation, and with a fierce resistance to the inclusion of humanity into the general evolutionary story, which prompted them to continue to identify themselves as non- or anti-Darwinian even where their actual beliefs differed little from some of Darwin’s most active supporters. After his death Darwin the man and scientist was recuperated, but ascription to his ideas remained at best partial and hesitant. It was among the younger readers – those born in the 1830s and 1840s sometimes slowly, and those born after 1845 generally much more rapidly or as a matter of course – that Darwinian convictions flourished. The balance of opinion in respect of Darwin and evolution did change over time, but more as a feature of generational churn than of individual conversion.

Implications

If the sorts of generational dynamics and structures that the book seeks to uncover did exist, then the implications of this stretch well beyond the history of evolutionary belief, and indeed the bounds of the Victorian and Edwardian periods. At a prosaic level, they suggest that we need to start using ‘generation’ in less cavalier fashion, and to be a great deal more attentive to the age and hence generational location of the individuals we study or seek to deploy for evidentiary or argumentative purposes. We can no longer pluck individuals out of their context and use them to demonstrate a general shift. We can no longer deploy anonymous texts as unproblematic representations of opinion at a particular moment or of a particular group. We need to be aware of the double chronologies at work: the ‘thin’ chronologies of historical time, but also the more lumpy chronologies of individual biography.

More profoundly, we are asked to reimagine the histories of cultural formations, to think about their generational dynamics, the differences between inter-generational objectives of a group like the Synthetic Society, and the concentrated generational solidarities of coteries such as the Lux Mundi group. To think about the way disciplinary knowledge, say the spread of Pragmatism in British philosophy, or the particular nature of British sociology as it institutionalised in the Edwardian period, is aligned generationally. In some speculative concluding remarks the author goes as far as to suggest that generational perspectives demand that we re-examine our notions of historical time and of the nature of historical change. If even a society without strong generational identities such as Victorian Britain demonstrates powerful generational patterns, this only underlines the character of periods not as separate and entirely sui generis boxes, but rather as shifting configurations of layers, elements carried forward from the past and others anticipating the future. From this perspective, all cultural change becomes less a linear progression and more a multi-part score, an matter of the ebb and flow of voices, a set of harmonic phases.

Clearly a single study, even of this length, can only be a start. Readers will have to come to their own conclusions on the extent to which the book convinces. But they will not be able to refute it with counter-example. No attempt is made to shy away from the abundance of exceptions; but the argument is to be won by preponderances not instances. By the same token, given the slipperiness of responses to Darwinian ideas, and the scope left for confirmation bias, it will only be through the demonstration of statistically verifiable generational effects that Darwinism’s Generations’ schema will be given a firm base. The identification of behaviours more amenable to quantitative investigation would be an important step in the right direction, along with a more precise statistical method for locating the effective boundaries of generational cohorts. Current developments in corpus linguistics, network analysis and record linkage all offer promising ways to take generational explanations further. But for now Darwinism’s Generations offers a thesis which it is hoped will force scholars to be less cavalier in their illustration and example, and more cautious – or at least more contextual – in their selection of exemplary cases, and perhaps more generational in their address to the structuring forces of society and culture.

Darwinism’s Generations is available via the Oxford Academic digital platform, to those with access to a subscription; the address is https://academic.oup.com/book/58805

I discovered you on blue skies last evening and came to your website. Don’t feel bad about writing a review of your own book because it really highlights your intentions and an overview from the perspective of the author. I am an artist and went to a critique group with a painting, unfortunately they didn’t know the meaning of the painting and therefore missed the whole point. My explanation of the intent changed their view. I love the concept of generational changes in attitude toward a theory.

LikeLike